Until around the middle of the twentieth century, ‘conservation,’ ‘nature,’ and ‘the environment’ were not yet watchwords in a popular lexicon for anxiety and action in the face of environmental destruction. Today, these words are freighted with heightened urgency, but they also carry a widely shared desire to view nature as static, that is, to fix it in an idealized time immemorial. The well-meaning politics and beliefs sustaining this rearguard view of the natural world are the potent forces behind policies and practices known as ‘fortress conservation.’ This conservation model, aimed at returning natural landscapes, flora, and fauna to a pristine, putatively originary state, alienates forest-dwelling communities, in countries such as India, and expedites nature’s expropriation on social media and in luxury tourism.

In India, the tiger (Panthera Tigris) is the national animal and by far the country’s most iconic image of conservation. You might say that the animal is paid in kind through an allocation of 70 percent of the central government’s protected-area budget to India’s 50 tiger reserves; the remaining 30 percent is spread across 567 protected areas. You might also observe that tigers and photography are natural bedfellows and ground this insight in the illustrated pages of environmental reports, publicity for safari holidays, or wildlife-related feeds on Instagram. The tiger stilled in the photographic frame is an extraordinary apparition. But these images potentially inculcate ‘wild’ fantasies about experiences in places of wilderness saved just in time from prior human occupation and future encroachment. Never mind that for tourists to bear witness on Instagram to uninhabited wildernesses, the human footprint is a given. Or that the presence of people in India’s forested areas for centuries contradict the endpoint of returning national parks to their natural state of uninhabited wilderness. In the worst-case scenario, these images deliver a salvation narrative that presents any community dependent on the forest for livelihood as an environmental threat and diverts attention from industries responsible for habitat fragmentation.

Keeping the human cost and economic capital advantages of romanticizing nature in full view, this series investigates tiger photography across almost two centuries in India. The four-part series is an exploration of the human desires driving prolific production and avid consumption of tiger photo-imagery. For instance, the slain tiger at the feet of the hunter in colonial-era photography can tell us much about how masculinity and imperialism is visually staged to justify the British presence in India. Today’s tiger imagery on social media, on the other hand, converts wilderness into a seemingly valuable commodity and makes visible capitalist logic as a party to, but not always determining, conservation practices. The tiger photograph then offers a medium for understanding changes in the human relationship with the natural environment.

When Indira Gandhi’s Congress government, under pressure from home and conservation organizations abroad, notably IUCN (the International Union of Conservation of Nature) and WWF (World Wildlife Fund), introduced the Wildlife Protection Act (1972), and Project Tiger (1973), hunting, poaching, and habitat destruction had decimated India’s tiger population. At the turn of the 20th century, an estimated 40,000 tigers inhabited India’s forested areas. By the 1970s that number had fallen nearer to 1000. After independence in 1947, mining and hydroelectric projects led to extensive habitat loss for the tiger and other wildlife, while the hunt itself continued to be a source of revenue through tourism. Travel agencies lured international and local tourists with the promise of princely hunting holidays and tigers that, thanks to a thriving business in taxidermy, would make ‘the best trophies.’

The colonial period was especially catastrophic for the tiger. British officers and officials, fancying themselves as the ‘New Mughals,’ were quick to recognize the advantages available to Mughal rulers deploying ‘the symbology of power and the power of symbology’ (Anand S. Pandian, 2001) around hunting practices. Having imbibed from Indian rulers the iconic power of the tiger, the British Raj used ‘trophy shots’ of dead tigers to present the hunt as an embodiment of colonial masculinity and imperialism, and impress upon a local population the formidable power of the colonial state. The photo-op offered a chance to maximize the symbology of the dead tiger. For this reason, most of these images scarcely conceal a small stick tucked perpendicular beneath the dead animal’s jawline to prevent it from slumping to the ground.

Shooting a tiger often served as a coming-of-age ritual for young Indian princes. Not surprisingly then, it became a rite of passage for British officers and officials. “Any perusal of the voluminous colonial hunting narratives and memoirs,” Anand S. Pandian writes, “would suggest that the slaying of a man-eater was almost a ‘rite of passage’ for these men: each had their own story to report and glory in.” Around this same period, the British were responsible for popularizing the hunt, making it accessible to a public unaccustomed to hunting and without affiliations to royal ranks and gentry in India and English officers and gentlemen. They incentivized a newly enfranchised hunting community with bounties for slain tigers. The colonizer’s intent is articulated in an East India Company revenue letter written in 1826 describing the need to encourage Indian hunters to be more ‘active and enterprising’ at killing tigers (the letter is quoted in a 2006 article aptly titled ‘‘’Face Him Like a Briton’: Tiger Hunting, Imperialism, and British Masculinity in Colonial India, 1800-1875″). Viewed through the lens of colonial paternalism, the hunt was one of many benign acts designed to protect the rural populace from so-called man-eating tigers. Profit motives behind the de facto policy of eliminating the tiger population were borne out in prodigious timber sales and conversion of forest to agricultural land.

After the Wildlife Protection Act, the tiger’s natural capital was based on it being alive instead of dead. Before this, though, photography left a ghastly trace of tiger hunting’s body count. Each colonial period ‘trophy shot’ is alike in so far as it undoes the advantage belonging to the tiger in a natural contest, reversing the hierarchy between human and apex predator that pertains in the wild. These images flagrantly flaunt man’s ability to overcome natural disadvantage to subdue or even destroy nature. Seen from a vantage point in the contemporary world, photographs of dead tigers, draping the ground beneath the feet of men and occasionally women belonging to Indian and British ruling elites, are relics not only from another time but from another universe. Yet to become a popular concept, conservation was still a little-known idea applied sometimes in settings where hunting stocks had fallen low enough to threaten future viability for the industry. The target audience for these images would have been able to relate the decline of blood sports to endangered animals but were unlikely to have understood the effect of species extinction on ecological balance. The moral world captured in these images is a faraway place also. Concern for the animal or shame at the prospect of what people would see in the photograph is absent. No more than conservation, one suspects animal cruelty was a little-known idea then as well.

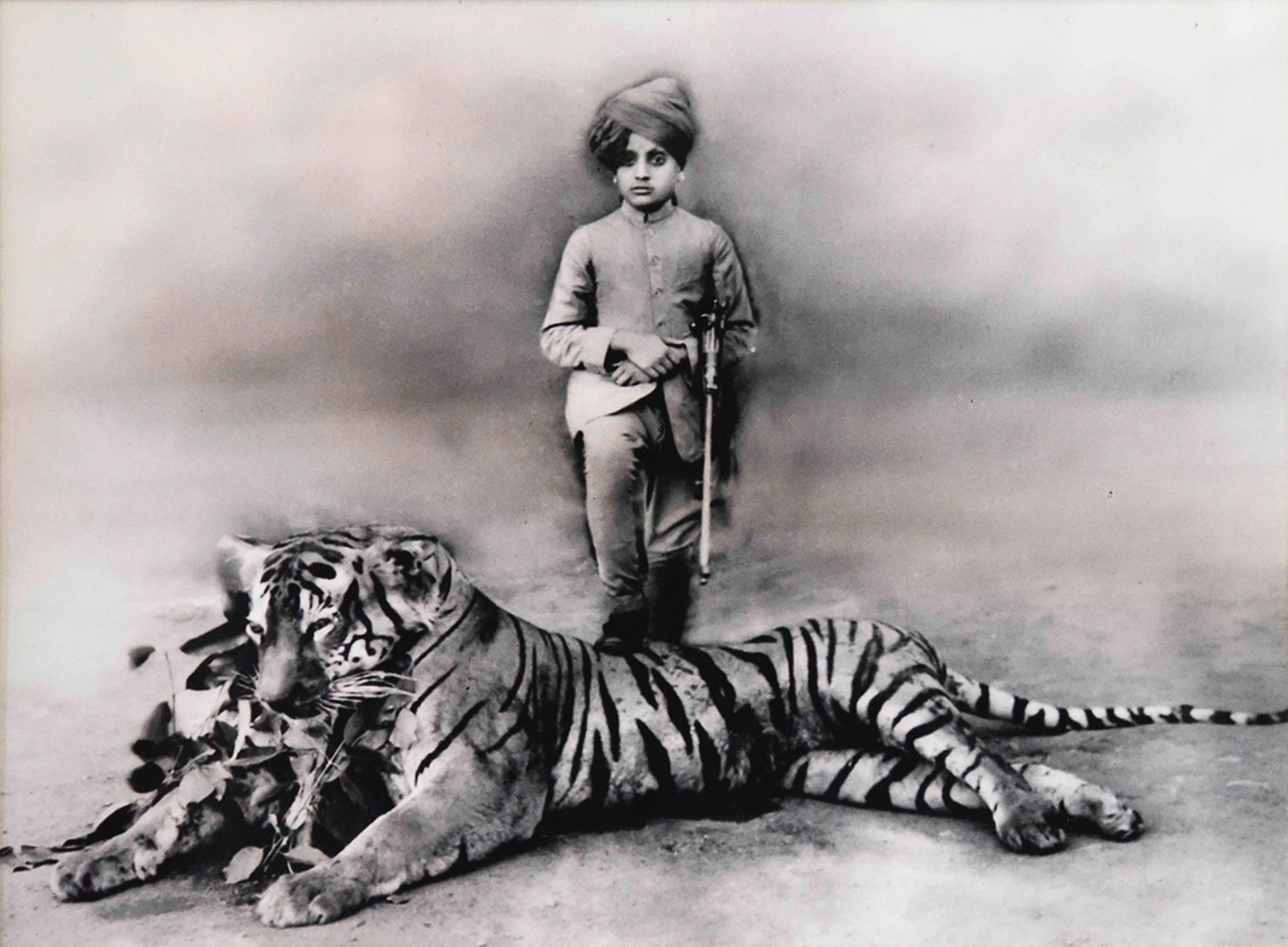

FIGURE 1: First tiger trophy of Manvendra Maharaja Narendra Singh at the age of eleven, 1926.

(Royal Collection, Panna)

The trope of the hunter’s foot resting or pointed at the tiger’s body is a recurrent feature in photo dispatches from shikar expeditions mounted in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In a photograph from 1926, belonging to the Royal Collection of Panna, Maharaja Narendra Singh, at the tender age of eleven, is shown in the dead center of the frame, his foot resting on the back of a dead tiger arranged to appear in a life-like pose. A small clutch of branches with some attached leaves prop the tiger into a semi-upright resting position and serve as a throwback to the natural habitat from where the animal has been irrevocably seized. Royal photographers involved in staging these photographs also captured hunts in progress. The camera was on hand when the tiger met its death and during its conversion into an object of display.

FIGURE 2: First tiger shot by HE Lord Curzon in India, Gwalior’ by Lala Deen Dayal, 1899,

from the album HE Lord Curzon’s first tour in India. (Courtesy of The British Library)

Lala Deen Dayal, one of the most sought-after royal photographers working during the height of India’s colonial period, photographed Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India (1898–1905), during various shikars spanning his stay in India, in a similar pose. One of Dayal’s images of Lord Curzon posing alongside Maharaja Sir Madho Rao Scindia of Gwalior in an indoor setting is part of an album titled ‘HE Lord Curzon’s first tour in India 1899’ in the British Library. Both men stand with folded hands and one foot resting on the body of a pair of tigers splayed out before them. This gesture of entitlement to the natural world recurs across many decades of tiger photography depicting imperial rulers in the princely states and officials representing the British crown. The fact that both men have chosen not to appear in hunting gear – Curzon is dressed up in coattails and the Maharaja of Gwalior in an anga and pagadi – suggests a mutual desire to convey the right and might of civilizing missions prevailing over savage nature. Reinforcing this agenda is a domestic setting for the photograph that transports the tigers from the jungle’s understory to the tiled floor of the Maharaja’s palace.

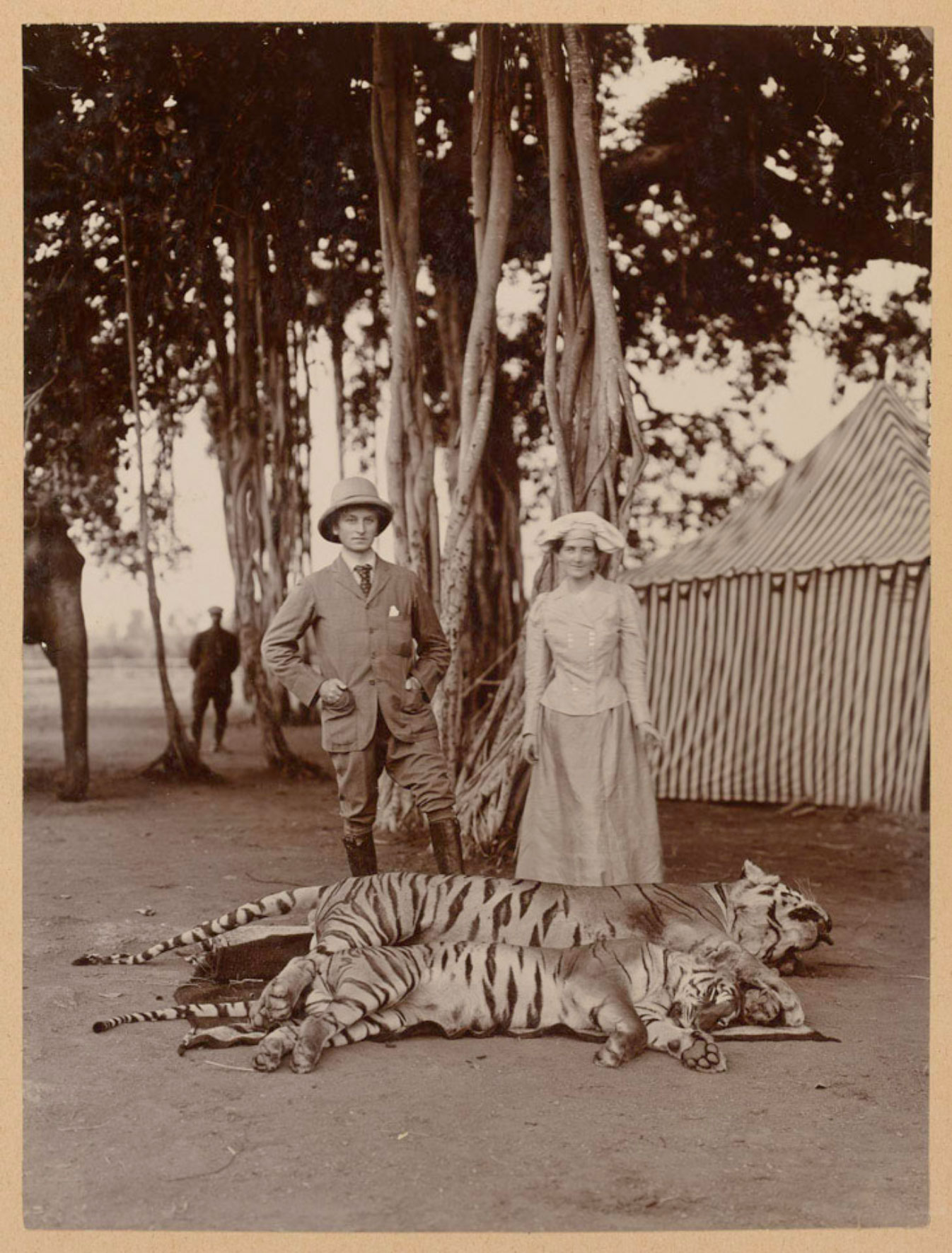

FIGURE 3: ‘Their Excellencies Lord and Lady Curzon with second day’s Trophy,’ 1902,

from the album Souvenir of the Visit of their Excellencies Lord and Lady Curzon to Hyderabad, Deccan,

by Deen Dayal & Sons. (Courtesy of the Alkazi Collection of Photography)

FIGURE 4: Lord and Lady Curzon, by Lala Deen Dayal, 1902,

from the Sir Hugh Shakespeare Barnes Collection. (Courtesy of The British Library)

In a slightly later set of photographs, taken in 1903, Dayal shoots Lord and Lady Curzon in a safari camp in Warangal District, Hyderabad. Two of these photos, shot during the same expedition on alternating days, are remarkably similar. Both frame a banyan tree and striped tent with circus-flair in the background; the couple is positioned immediately behind a tiger in one photograph and a pair of tigers in the other one; subjects are center-foregrounded in each photograph. Curzon’s pose is almost identical in each picture – not only are both hands in his jacket pockets, but both images also show a right hand that is half-in and half-out and a left leg that juts forward, gesturing towards the tiger. This gait is remarkably similar to the use of his leg in a gesture of possession described earlier. If the ‘evidence’ of the kill lying at Curzon’s feet already proves his masculinity, the simultaneous presence of his wife further emphasizes it. Nothing about the physical arrangement of the photo suggests that Lady Curzon is making any claim to ownership of the lifeless tiger. On the contrary, her presence seems contrived to bear witness to her husband’s hunting prowess, with her cinched in waist stressing a ‘delicate’ build that according to Victorian ideals of the time would have made her ill-designed for physical pursuits.

In time, many of the maharajas’ hunting reserves would become national parks housing tiger reserves. Before Ranthambore National Park became one of the most popular locations in India for tiger safari, it was controlled by the Maharaja of Jaipur’s hunting department. In another irony, the Jim Corbett National Park, equally well known for its population of Bengal tigers, was named after a British man who initially achieved prominence in India for his ability to capture and kill aged or infirm tigers prone to attacking villages. In these and other national parks in India, image hunters replace hunters with firearms. With an identity tied to a global conservation consciousness, and being at the center of Project Tiger, one of the country’s biggest mobilizations of resources and manpower in the service of species protection, the tiger is no longer hunted in the traditional sense. The long camera lenses used for ‘shooting’ though recall the long barrel of the hunter’s rifle, offering a reminder that although the tiger is protected from threats responsible for decimating its population in the past, it is still not being left to its own devices. This is the subject of the next essay in this series.

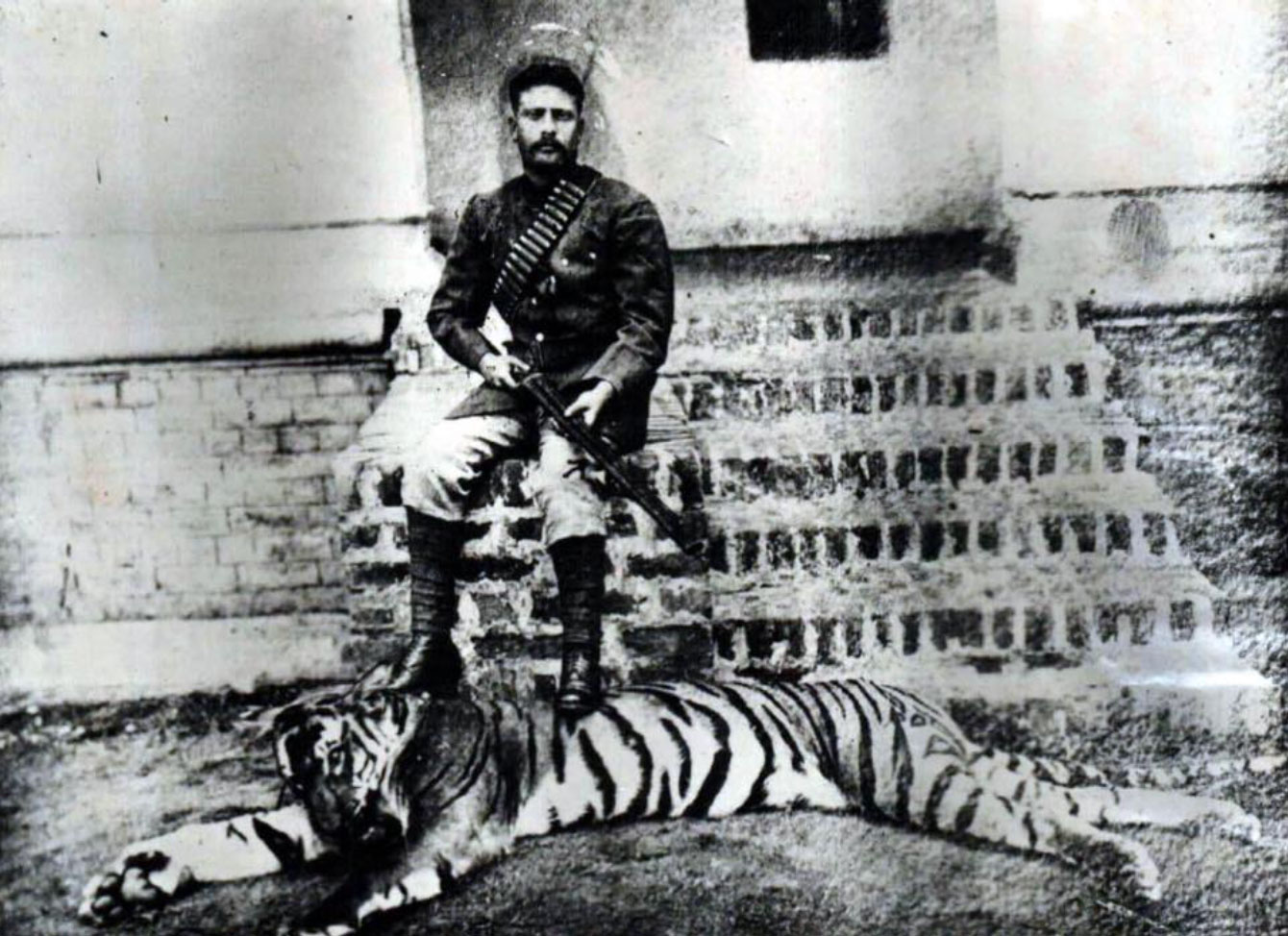

FIGURE 5: Ramendranarayan Roy, prince of Bhawal estate,

(currently Gazipur District, Bangladesh), unknown author. Public Domain.

Image Credits

Figure 1: First tiger trophy of Manvendra Maharaja Narendra Singh at the age of eleven, 1926, Royal Collection of Panna

Figure 2: First tiger shot by HE Lord Curzon in India, Gwalior’, 1899, from the album HE Lord Curzon’s first tour in India. (Courtesy of The British Library).

Figure 3: ‘Their Excellencies Lord and Lady Curzon with second day’s Trophy’ from the album Souvenir of the visit of their Excellencies Lord and Lady Curzon to Hyderabad, Deccan. Gelatin Silver Print, Photographers Ref. 18352, 1902, 263 x 204 mm. ACP: 97.19.0002(0045). Alkazi Collection of Photography

Figure 4: Lord and Lady Curzon, 1902, Courtesy of the British Library.

- Prof. Aileen Blaney, Associate Professor – Film Studies