MEDIA

Political Motives Trump Administrative Reasons: Tracing the History of District Creation in India

www.thewire.in | August 31, 2024While state formation in India has always been a contentious issue, with various communities demanding statehood since independence, there is very little public discourse on district formation within state administration. Public policy and administration rarely address the evolution of the 'district' in India.

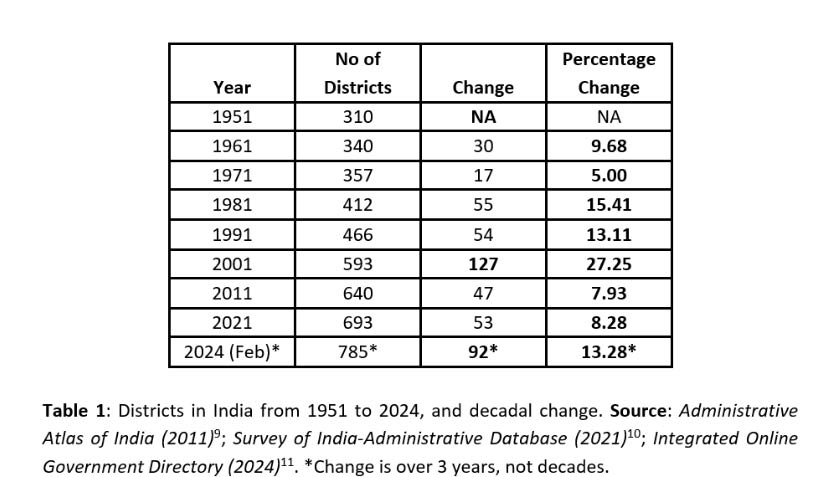

In 2022, Andhra Pradesh more than doubled its number of districts from 13 to 26 with a single executive order. Similarly, Rajasthan increased its number of districts from 33 to 50 in 2023 alone. Between 1951 and 2011, the number of districts in India surged from 310 to 640. More recently, from 2021 to February 2024, this number has jumped from 693 to an estimated 785.

The population and area of these districts vary significantly, with Dibang Valley housing just 8,004 people (2011) and Thane district surpassing 10 million. Similarly, the Kachchh district in Gujarat spans over 45,000 sq. km, dwarfing the Central district of Delhi, which covers only 21 sq. km as per the Census of India (2011) data. This vast disparity raises several critical questions:

While state formation in India has always been a contentious issue, with various communities demanding statehood since independence, there is very little public discourse on district formation within state administration. Public policy and administration rarely address the evolution of the ‘district’ in India. Why are districts split? What is the basis for creating new districts? Who bears the costs and who benefits? Does creating new districts necessarily lead to better administration?

The State and District Evolution Project, initiated by the Centre for Legislative Education and Research at FLAME University, seeks to address these questions. This project tracks the evolution of states and districts in India from pre-independence to the present day.

Through an analysis of district splits, mergers, and new creations at both national and state levels, this article explores the numerical changes, population, area, and density of Indian districts. Additionally, it delves into the demographic, spatial, and political factors influencing the creation or prevention of new districts.

Tracing the district story: Colonial creation to present

Historically, the district (by whatever name it was called) was created to enhance administrative efficiency and collection of tax. All feudal empires in India, from Mauryan (adhisthana in the North and Kurram in the South, managed by Rajuka’s) to Moghuls (Sarkars, headed by Fauzdar) had a form of decentralised administration at the district level for collection of taxes and implementation of administrative tasks at the local level.

The modern form of the district as an administrative unit came into being under Warren Hastings in 1772. The Office of Collector, set up by Warren Hastings then, had judicial, executive, and revenue powers. The post of Collector was retained as a permanent feature of local administration heading the offices of Revenue Administration, Civil Judge and Magistrate combined.

The same district-level model was taken forward post-independence. To this day, barring judicial duties, the Collector is held accountable for all executive and revenue-related functions and is also tasked with additional duties such as Maintaining law and order, Revenue collection, Land reforms, Planning and development, Excise duty (in some states such as MP ) and the role of the District Election Officer.

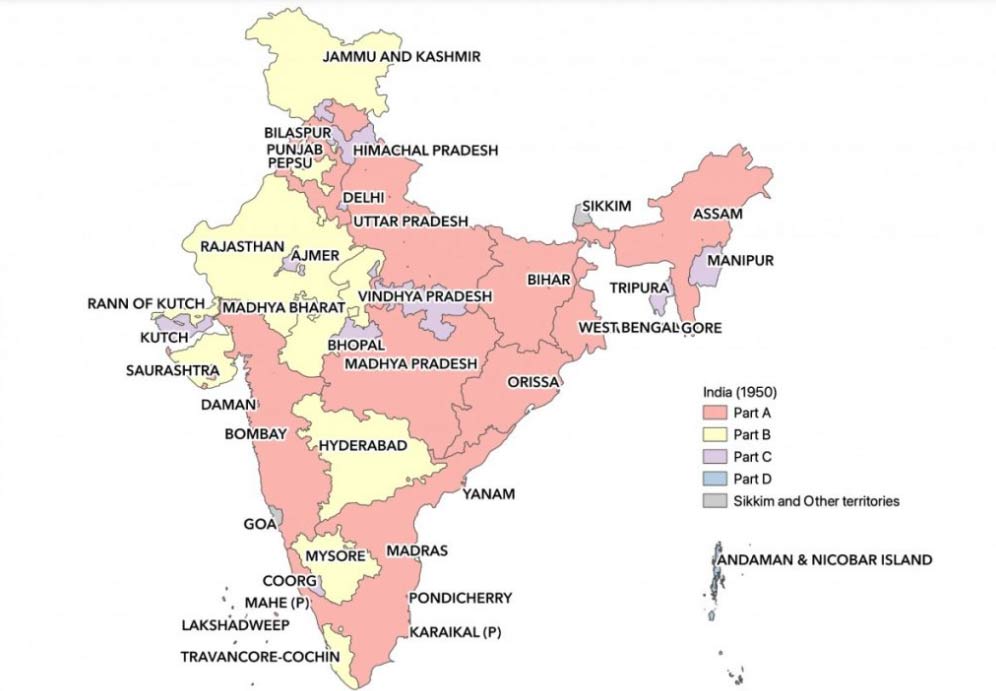

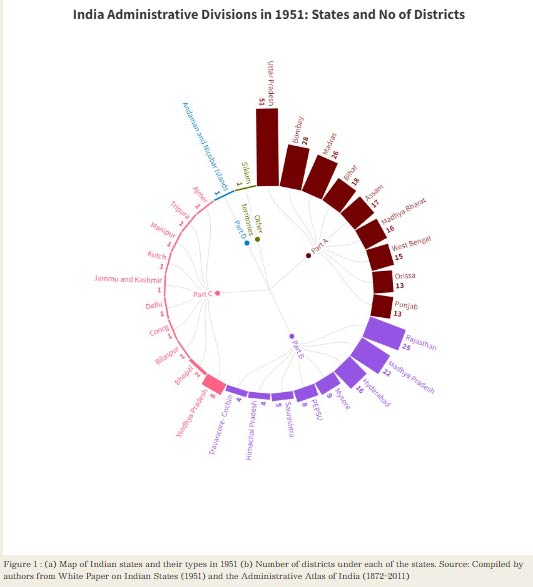

Figure 1 : (a) Map of Indian states and their types in 1951 (b) Number of districts under each of the states. Source: Compiled by authors from White Paper on Indian States (1951) and the Administrative Atlas of India (1872-2011)

Back in 1941, India under British administration consisted of British provinces and its districts and numerous princely estates and jagirs. Together they formed 424 larger administrative units – 202 princely states, 42 princely districts, and 180 British districts.

By 1951, efforts undertaken by the Indian government to consolidate these units resulted in 310 districts across 29 states (classified as Part A, B, C, and D). In 1956, administrative divisions in the country were linguistically re-organised as per the recommendations of the State Reorganisation Commission (SRC). The map formed thereafter can be called the foundational map for states of India.

By 1961, the states had achieved a structure resembling the present-day boundaries of India’s states, and since then, state administrative boundaries have remained relatively stable. However, the same cannot be said for districts in the country. Since the integration period, the union and respective state governments have frequently carried out the exercise of splitting the districts, renaming them, and occasionally merging or re-carving new districts.

Between 1961 and 2021, the number of districts in the country increased from 340 to 690, resulting in an average of 60 new districts per decade. In the decade 1991-2001, India saw the creation of 127 new districts, which is the highest since independence. More recently, between 2021 and 2024, 92 districts were added, taking the total to 785 (as of Feb, 2024).

The state governments in the name of ‘strengthening district administration’ have relied significantly on the creation of new districts. Notable cases of district creation in the last few decades include:

- Assam between 1981-1991, increased the districts from 10 to 23

- Orissa increased districts from 13 – 30 between 1991 to 2001

- NCT of Delhi- Post statehood (1992) created 8 new districts

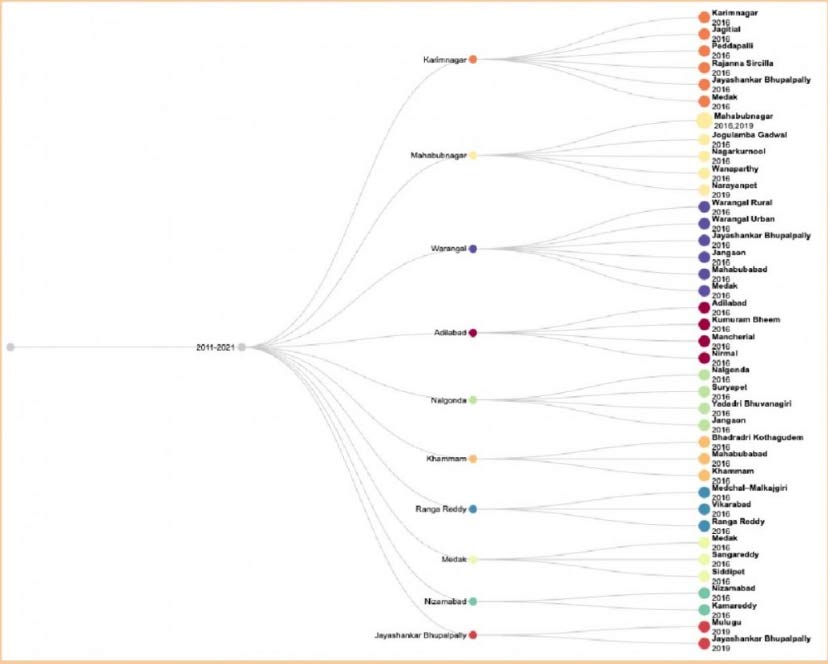

- Since its inception in 2014, Telangana has witnessed a threefold increase in its number of districts, growing from 10 to 33 by February 2024.

- Arunachal Pradesh, with a modest population of 13.8 lakhs as of the 2011 Census, added two new districts in February 2024, bringing its total to 28.

- In Telangana, the districts increased from 10 districts in 2016 to 33 in 2023

Figure 1: Illustration of District Splits in Telangana 2024-2021. Source: Analysis of media reports and publications by authors.

Consider this: In Assam, district creation and mergers have been at the mercy of political games by the Chief Ministers in power. In 2015, under Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi, five new districts were created, raising the total from 27 to 32. Majuli was added as a district in 2016. Under the new chief minister Himanta Sarma, Bajali and Tamulpur were created in 2020 and January 2022, respectively.

However, in December 2022, CM Sarma announced the merger of Biswanath, Bajali, Hojai, and Tamulpur with older districts as a temporary measure before the Election Commission’s delimitation process. Yet, on August 25, 2023, the CM reversed this decision, recreating the four merged districts, bringing Assam’s total district count to 35.

Between 1951 to 2024, India’s population has increased close to 4 fold (361 million to 1400 million), while the average district population has indeed increased only 2.2 fold from 1.16 million to 1.78 million, thereby justifying the creation of a large number of new districts in recent times.

On closer examination, however, we find that population has not been the primary criteria for district creation. Unlike parliamentary and assembly constituencies that are delimited based on the population (albeit – age-old 1971 Census data), or the Census definition of Urban areas, (based on population, density and the male agriculture workforce), the creation of a district does not seem to follow from well-defined criteria.

The Indian constitution does not feature a discussion on the norms for the creation of new districts. The power to create new districts or alter or abolish existing districts rests entirely with the respective State governments. The Centre does not have a role to play in the alteration of districts or the creation of new ones. Typically, the creation of a new district is done via issuance of an executive order in the state gazette or by passing a law in the State Assembly. This gives a free hand for state ministries to bifurcate, split boundaries, and merge districts at will, through a mere notification in the gazette.

Searching for a rationale for district creation: Experts view

District creation is a complex issue and therefore, it is argued that besides the population, density, and area, district creation may be based upon factors beyond population size or density, that aren’t directly related to administrative convenience or efficiency. Often the creation of a district is announced by the state government (through executive/government order of passing law in the assembly) stating ‘administrative convenience’, often masks other underlying motives.

Our interactions with a former bureaucrat (referred to as Mr. X) from Gujarat revealed that the creation of Patan from Mahesana and Banaskantha, and Navsari from Valsad in 1997, under the then Chief Minister, offered no administrative advantages and appeared politically driven. These decisions notably favoured regions linked to influential political figures.

Similarly, the 2013 bifurcation of Bhavnagar into Botad and Bhavnagar was described by the former bureaucrat as having no clear administrative purpose and seemingly carried out to please a minister with ties to prominent industrialists (names withheld on request). Often, identity issues, rather than administrative efficiency, determine the creation of a district.

For instance, Mahisagar district was created by splitting Kheda and adding a taluka from Panch Mahals to prevent the domination of one community by mixing them with tribal groups. The creation of Dahod from Panch Mahals and Chota Udepur from Vadodara, according to the former bureaucrat, was aimed at separating tribal-dominated areas in urban districts.

A former civil servant (referred to as Mr. Y) from Himachal Pradesh gave us the following insights. Himachal Pradesh’s districts have remained stable since 1972, but there has been significant division at the sub-district level, with the number of tehsils increasing from around 40 in the 1960s to about 172 today. Local lobbies and interests often prevent the dividing of districts.

Despite possessing a relatively large area or population, some districts resist division due to the local perception of greater clout as a large district. Large districts like Lahaul and Spiti present unique administrative challenges due to their geography.

Separated by a high mountain pass that is impassable in winter, Lahaul is administered from Keylong by the District Collector called Deputy commissioner in HP, while Spiti is managed from Kaza by an Additional Deputy Commissioner with equivalent powers. In contrast, the residents of Kangra district take pride in its large population and the significant influence they wield in Himachal Pradesh’s administration, resisting any attempts to divide the district.

Mr. Y, who has also spent time in the North East in different capacities, says that historical legacy plays an equally important role in the creation of districts in the country. Prior to independence, in North Eastern States (barring current Assam) most land was communally held by tribal groups, and the British did not conduct land surveys or establish tehsils in these regions.

Consequently, many North Eastern states do not have tehsils or a structured land administration system till date. This has resulted in as many as 28 districts (as of February 2024) in the state of Arunachal Pradesh, some with populations as low as 8,000 as a patronage-based response to enable greater access to administration.

In the south, Mahe, a small district within Puducherry Union Territory, is geographically surrounded by Kerala but shares a distinct French colonial history with Puducherry, not Kerala. Despite its small size and population, Mahe’s residents prefer to stay connected to Puducherry, highlighting the importance of historical ties over demographic characteristics.

In Maharashtra, a former civil servant (referred to as Mr. Z), shared the district politics in the state. He believes that splitting districts generally brings people closer to administration but incurs significant administrative costs. For instance, Ahmednagar, one of Maharashtra’s largest districts, has long-standing demands for a split into North and South due to the long travel times to the city centre, yet this demand remains unfulfilled.

The creation of Palghar, announced in the early 2000s and realised only in 2014, was necessary due to Thane’s enormous population and diverse areas. However, many offices are still not established. Pune remains largely unchanged despite proposals, such as the failed Baramati district creation due to potential political dominance by the Pawar family.

Pune’s case for division is strong due to its metropolitan, rural, and tribal areas, yet regional development and fund distribution remain unequal. Cities, having multiple power centres, further complicate administrative decisions. The demand to create the Malegaon district from Nashik is resisted due to its Muslim majority and potential vote bank implications.

All the three bureaucrats opined that creating new districts imposes significant administrative costs, requiring new offices (Offices of collectorate, other admin office, District courts, zilla parishad office etc), additional manpower, updation of records, and data separation. Although draft notifications on district creation invite objections, most are overruled.

Mr. Y emphasised that the politics of patronage significantly influences all administrative decisions, favouring tangible developments like new schemes and infrastructure over fundamental reforms and structural changes.

While district creation is often justified as a step towards decentralisation, it does not effectively achieve this goal. Instead, district administration remains an extension of state administration, providing more government employment opportunities and prestige for local figures. Mr. Z suggests setting norms for district creation, including assembly voting, district-wide voting across all panchayat levels, and considering factors like geographical area, population, and number of villages.

Need for common, but differentiated norms for district creation

Our analysis of the evolution of districts in India post-independence and interactions with the bureaucrats reveals that there are no clear demographic and geographic norms for splitting and creation of new districts. Commonly, politicians justify the creation of new districts by claiming that smaller districts allow for improved administrative efficiency and better governance. But we have little convincing evidence to prove that smaller districts are necessarily better governed. District splits are often found to be guided by political motives.

This is particularly evident from the sudden expansion of districts witnessed in the states of Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana through mere executive orders by state governments with little consultation of people on ground. In the absence of codified criteria for the creation of districts, the solidification of the district identity takes precedence over crucial developmental projects and capacity-building initiatives.

Proposed reforms vis-a-vis district administration

The modern-Indian district is the link between the centre, state, and the citizens. Located at the bottom rung of the hierarchy, the district continues to remain crucial since the implementation of all developmental programmes initiated by the state and the central governments is carried out at the level of the district.

Although district creation brings state administration closer to the people, it also poses a high cost to the state exchequer. A whole body of state machinery needs to be created at the district level such as the office of district collector/magistrate/commissioner (nomenclature varies from state to state), multiple departments under it, district courts, and new zilla parishads.

Today the role of the District Collector has expanded substantially from the colonial era (although some roles have also been done away with). The District Collector in the present day fulfils multiple positions which include but aren’t limited to – Head of District Administration, District Magistrate, District Development Officer and District Election Officer.

This has resulted in the concentration of responsibilities and power within the hands of the Collector and made the position of the Collector more crucial than it was in the pre-independence era. Creation of new districts gives the state more arms to pursue its policies and agendas, but it does not necessarily translate into decentralisation, as the third tier of governments (Panchayats at village/taluka/districts, and the urban municipality/municipal corporations) are not empowered along with it.

The three Ds of Decentralization, namely, Deconcentration, Delegation and Devolution refer to different levels of decentralisation. Devolution, which involves a shift of power to the sub-national units, aligns with the true spirit of Decentralization. The concentration of power in the hands of Collectors in the absence of Devolution has led to a trend wherein we are increasingly witnessing District Collectors operating largely as agents of the state and puppets in the hands of political party leaders (as reflected in frequent and arbitrary transfers and shifting departments).

A lack of devolution of powers entrusted with the Collector complicates the situation further as a newly appointed. A collector is burdened with responsibilities that hardly spare time for developmental initiatives that are typically promised every time a new district is created. The deliberative body of Zilla Parishad remains subordinate to the Office of the Collector. Public consultation remains absent, be it the discussion of the district’s development or the concerns surrounding the creation of new districts.

In light of these concerns, we propose few much-needed reforms for managing the fragility of our districts:

- Devolution of the Collector’s Duties to Zilla Parishad: A better approach to manage district administration would be to devolve functions to the Zilla Parishad, that is an elected body as, instead of burdening the Collector. We need to break away from our colonial legacy of entrusting all powers to the Collector. The Collector’s power needs to be devolved to facilitate capacity building as opposed to arbitrarily splitting districts under the garb of decentralisation and better governance.

- Codification of Rules for District Creation: The creation of new districts needs to follow common and differentiated criteria, based on a combination of demographic indicators and relevant social and historical parameters as deemed fit. The entity can simultaneously look into the proposals for new districts and decide which ones need to be approved and which don’t. This entity must be held accountable to the public. Public and stakeholder consultation needs to be undertaken before the finalisation and creation of any new district.

This work was supported by the FLAME Centre for Legislative Education and Research.

Mehr Kalra is a former research associate and freelance consultant to the India State and District evolution project. Her areas of interest include gender, public policy, and urban studies. She has previously interned with CPC Analytics, Aajeevika Bureau and the Netherlands-based WageIndicator Foundation.

Prof. Shivakumar Jolad is Faculty of Public Policy at FLAME University. His research interests include social policies focused on education, migration, and human development. He also works on local governance, quantitative study of the constitutional and administrative history of India.

(Source:- https://thewire.in/government/drawing-lines-searching-for-a-rationale-in-district-creation-in-india )