Summary

China's High-Speed Rail (HSR) network, is the world's largest and most used, offering low fares and reduced travel times. Despite financial challenges and significant debt, the HSR system continues to expand and improve, leveraging advanced technology and strategic international exports. The HSR network has profoundly impacted China's regional development, economic growth, and global infrastructure leadership.

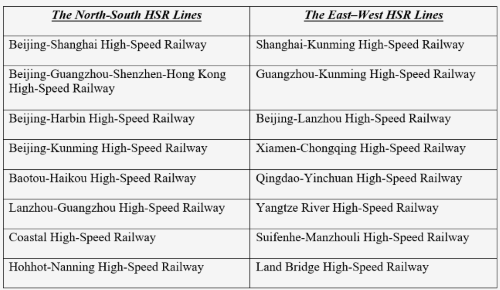

China’s High-Speed Railways (HSR) cover over 45,000 kilometres and are evenly spread throughout the most densely populated areas of China. China’s HSR connects 33 out of the 34 provinces, making it the world’s longest and most extensively used network. The network of railways consists of 8 vertical (North-South) and 8 horizontal (East-West) lines. HSR lines cater to the public by charging low fares and enhancing accessibility and reducing travel time between urban centres.

What is HSR?

HSR is a passenger train that travels at a speed of 200-350 km/hr. These trains use steel wheels to move along a track of steel rails. The head of the train has an aerodynamic build, which minimises air-resistance and is made of a special material called “super thin large hollow aluminium”, enabling the head to achieve a perfect weight, where it is neither too heavy to reduce speed nor too light to withstand the air pressure. Unlike conventional trains, which have only one engine in the front that pulls the entire train, HSR trains have four to six locomotives instead of one. This divides the load evenly, enabling the trains to gain higher speeds with ease. The bogie system, essentially the legs of the train, helps the train move smoothly on the tracks and is also made of high-strength steel to withstand extreme temperatures. The primary differences between HSR and conventional trains lie in their speed capabilities, specialised technology and infrastructure designed specifically to support high-speed operations.

The History

After experiencing Japan's Shinkansen in 1978, China’s then Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping was inspired to develop a similar high-speed rail system in China. With trains averaging just 48.1 km/hr in 1993, the government launched the "Speed Up" Campaign from 1997 to 2007. This initiative, overseen by the Ministry of Railways, aimed to improve train speeds in six phases. Beginning with track upgrades, it culminated in the introduction of 58 High-Speed Rail (HSR) lines, totalling 158 operational trains by late 2007, capable of speeds up to 250 km/hr.

On August 1, 2008, China inaugurated its first HSR line, the Beijing-Tianjin route, marking the start of rapid expansion. However, the Wenzhou train collision in 2011, caused by lightning striking a train, resulted in 40 deaths and heightened concerns about China's high-speed rail safety and management. Following the accident, the Chinese government suspended new railway project approvals and launched safety checks, leading to a slowdown in financing and construction. Despite these setbacks, investments in high-speed rail were renewed in 2012 to stimulate the economy, resulting in the opening of new lines and a rebound in ridership. By 2014, high-speed rail expansion accelerated, with numerous new lines approved by the central government. Moreover, the export of HSR goods to other countries was emphasised as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Turkey was the first country to which China exported its high-speed trains. In 2014, China won a contract to supply 10 high-speed trains for Turkey's Ankara-Istanbul line. The project was part-financed by $750 million in loans from China, including $500 million in favourable terms, aiding the push for HSR projects in developing countries. With the introduction of the Fuxing series of trains in 2017, some lines have resumed operations of trains going 350 km/h, contributing to the continued growth of China's high-speed rail network, which reached 37,900 km in length by the end of 2020. Remarkably, China now holds two-thirds of the world's total HSR infrastructure, achieved in just over a decade.

The Technology

How has China been able to develop its HSR in a relatively short span of time? China leveraged technology transfer agreements with foreign companies like Kawasaki of Japan and Siemens of Germany to begin its HSR program. Since Japan already had HSR built and running before China, Kawasaki, the manufacture of Shinkansen trains, facilitated the transfer of technology to China South Locomotive and Rolling Stock (CSR), a state-owned company, in 2004. Their $740 million agreement involved both the transfer of technology as well as the practical knowledge surrounding the manufacturing of HSR. Similarly, Siemens also came to an agreement with China CNR Corporation Limited in 2005 to build a rail line between Beijing and Taiwan, which was China’s first HSR. Siemens built three high speed trains in Germany and 57 in China. This localised production facilitated the rapid expansion of China's HSR manufacturing sector.

China is currently employing artificial intelligence to manage and maintain its HSR network. This AI system, located in Beijing, processes vast amounts of real-time data from across the country. It can notify maintenance teams of potential issues within 40 minutes with 95% accuracy, allowing for quick fixes. This has resulted in an 80% reduction in minor track faults and no major track problems over the past year. It predicts issues before they arise, enabling timely and precise maintenance, which enhances the safety and efficiency of the rail system. The AI system also helps mitigate the effects of strong winds on tracks and bridges, ensuring smooth and safe train operations.

The Economics

Surprisingly, the construction cost of China’s HSR is at most two-third of that in other countries. For example, HSR construction in Europe is estimated to have a higher unit cost, ranging from US $25-39 million per kilometre. In contrast, California's HSR project incurred costs as high as US $52 million per kilometre. China’s ability to build HSR at lower costs is because of several reasons. First, they quickly developed the skills and used new methods to build the rail lines efficiently. Second, labour costs in China are lower, and they use standard designs to save money. Also, because China builds a lot of HSR lines, they can spread out the costs over many projects, making each one cheaper. These factors have made it easier for China to expand its HSR network quickly and affordably. For projects with a design speed of 350 km/h, the unit cost ranged between 94-183 million yuan per kilometre, reflecting the need for advanced infrastructure to support high-speed operations. Conversely, for Passenger Dedicated Lines (PDLs) with a design speed of 250 km/h, the unit cost typically ranged from 70-169 million yuan per kilometre, indicating a slightly lower but still substantial investment in HSR infrastructure.

Examples of HSR projects in China provide insights into the varying costs associated with different routes. For instance, the Beijing-Tianjin HSR, which includes two mega stations, incurred a unit cost of 183 million yuan per kilometre. In contrast, the Shanghai-Hangzhou HSR, characterised by significant bridge construction and land acquisition costs, had a unit cost of 177 million yuan per kilometre. These examples highlight the varying costs involved in HSR construction projects across different regions of China.

Revenue and Profitability

One would typically assume that if such a large network was developed in a cost-effective manner, the revenue would outweigh the costs, but that isn’t the case. China Railway is facing significant financial burdens in the form of limited profitability, interest payments and overall debt. The company's total debt reached 6.04 trillion yuan ($890 billion) by September 2022, which is about 5% of China's GDP. Moreover, the company's passenger business has suffered losses due to reduced demand during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first nine months of 2022, China Railway reported net losses of 94.7 billion yuan, with sales falling by 1%. Moreover, data from the country's Ministry of Finance indicates that the total local government debt stood at 40.74 trillion yuan ($5.82 trillion) by the end of 2023. Despite these financial challenges, the government continues to prioritise new construction over debt repayment. The cost of extending the high-speed rail network is estimated to be around 120-130 million yuan per kilometre, requiring significant investment to build more lines. While efforts are being made to improve the performance of the freight business, doubts remain about whether introducing private-sector funds will effectively address the financial issues faced by China Railway.

A study from 2019, conducted by The World Bank found that China's high-speed rail network had an annual economic return of 8% in 2015. This study also highlighted various advantages such as faster travel times, improved safety, better tourism and labour opportunities, and reduced congestion, accidents, and greenhouse emissions. A similar study in 2020 estimated that the net benefit of the high-speed rail system to the Chinese economy was around $378 billion, with an annual return on investment of 6.5%. Recently, China has sharply increased fares for four major bullet train lines to address rising costs and heavy debts. The fare increases will take effect on June 15, 2024 and they aim to alleviate the financial strain on the CSR Group and its joint ventures. The fare hikes have sparked considerable discussion on social media, with many expressing discontent over stagnant wages and declining real estate prices.

The Need for Speed

The aim to develop the fastest train in the world has been set by the Chinese government who views HSR achievements as indications of China’s status as a developed country. The Shanghai Maglev train is the fastest in the world, designed to have a top speed of 600km/hr and recording a speed of 431km/hr. The Maglev train does not have wheels, and uses magnetic levitation to move without touching the ground. The train was produced in Germany through a joint venture between Siemens and Thyssenkrupp, with electrification developed by Vahle Inc. China also claims it is environmentally friendly since it produces no waste gas.

Construction of the Shanghai Maglev line started on March 1, 2001, and public commercial service began on January 1, 2004. The train runs between Long yang Road and Pudong International Airport with a total length of 30 kilometres, a journey that lasts 8 minutes and costs 50 yuan. This train is owned and operated by Shanghai’s city government.

Exports of HSR

China's emergence as a global leader in HSR technology began with its landmark export to Turkey in 2005, solidifying its position in the international railway market. Since then, China has expanded its HSR exports across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, showcasing its capability in delivering advanced railway systems worldwide. In Saudi Arabia, the Haramain Express project marked a significant milestone with the completion of the Middle East’s first double-track electrified high-speed railway by China Railway 18th Bureau Group, operational since 2018. The railway significantly reduced travel time between Mecca and Madinah, essential for transporting millions of pilgrims annually during Hajj and Umrah seasons.

Expanding into Southeast Asia, China exported its HSR technology to Thailand in 2017 through the China-Thailand Railway project, facilitating the country's first standard-gauge high-speed railway network. In Pakistan, China announced its export of 160 km/h high-speed train technology, with an initial shipment of 46 carriages completed on November 3, 2022, highlighting deepening bilateral cooperation in advancing transportation infrastructure. These exports collectively underscore China’s strategic role in global infrastructure development, leveraging its advanced HSR technology to enhance regional connectivity and solidify its leadership in the global railway industry.

Economic Significance of HSR

HSR in China has stimulated regional development and reduced travel time. It has increased productivity by enhancing travel efficiency and connectivity for the public. It has also boosted the tourism industry by making distant locations more accessible. Moreover, improved connectivity has facilitated business operations between urban centres, leading to economic growth in previously underdeveloped areas. The expansion has not only involved the development of new urban areas in smaller to medium-sized cities but also strategically placed HSR stations in undeveloped zones. This initiative promotes urban growth through integrated development plans known as "HSR new towns," which aim to generate substantial revenue from land sales, although success varies depending on infrastructure and market conditions. Moreover, HSR plays a crucial role in China's urbanisation strategy by serving as a vital transport backbone. It facilitates the decentralization of talent, technology, and economic activities to smaller cities, thereby alleviating the pressures of overcrowding, environmental challenges, and resource constraints typically associated with megacities. This strategy enhances overall business efficiency and urban living standards across the country.

The development of HSR aligns closely with China's broader socioeconomic goals, including poverty alleviation and regional economic convergence. By integrating economically diverse regions and improving transport connectivity, HSR supports government initiatives aimed at reducing regional disparities and fostering inclusive growth. Studies highlight the positive impact of HSR in promoting economic convergence across provinces, underscoring its pivotal role in China's strategic efforts to achieve balanced and sustainable development. In terms of competition, HSR has effectively competed with airlines for trips up to 1,200 kilometres. HSR is often cheaper and, for these distances, arguably more efficient. Passengers benefit from shorter travel times and greater convenience, as HSR stations are typically more centrally located than airports. For distances beyond 1,200 kilometres, airlines still hold an advantage due to their speed, making them a better option for long-distance travel.

Author

Kriti Rai

Undergraduate student at FLAME University pursuing Data Science and Economics.