Summary

China has a unique one-party system of governance that allows the existence of multiple other democratic parties. These parties do not have the opportunity to come to power, but certain provisions allow them to participate in Chinese policy-making and governance.

Overview on Political Parties in China

The Chinese political system is uniquely characterised by the supremacy of a single party – the Communist Party of China (CPC). However, China has eight other legally recognised political parties that have been integrated into the legislative system. Since China does not follow conventional democratic governance model the role of non-ruling political parties is very limited compared to opposition parties in democratic countries. In China, parties may advise or at times, offer criticism to the incumbent party, i.e. the CPC, but they play a minimal role in decision making, which is done by CPC bodies such as the Central Committee and the Politburo Standing Committee.

The following are the eight legally recognised political parties of China: Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang (RCCK), China Democratic League (CDL), China National Democratic Construction Association (CNDCA), China Association for Promoting Democracy (CAPD), Chinese Peasants and Workers Democratic Party (CPWDP), China Zhi Gong Party (CZGP), Jiusan Society and Taiwan Democratic Self-Government League (TDSGL).

Political Party |

Year Founded |

Membership Group |

Brief Overview |

|

Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang |

1948 |

Comprises members with strong ties to Taiwan and cross-strait businesses |

Formerly the Kuomintang (Nationalist party of China aka KMT). Founded in Hong Kong as a splinter group from the KMT |

|

China Democratic League |

1941 |

Comprises intellectuals from the fields of science, technology, education and culture |

Founded by prominent intellectuals to counter the second Sino-Japanese war aggressions |

|

China National Democratic Construction Association |

1945 |

Primarily comprises of businesspeople, industrialists and entrepreneurs |

Founded in the wake of the second Sino-Japanese war by prominent industrialists and businesspeople of the time |

|

China Association for Promoting Democracy |

1945 |

Intellectuals from education, culture, science and publishing |

Founded in Shanghai in the wake of the Second Sino-Japanese war by intellectuals primarily from the fields of education and culture |

|

Chinese Peasants and Workers Democratic Party |

1930 |

Comprises primarily of intellectuals from the medical industry |

Formed in Shanghai in the wake of the first civil war between the CPC and the Kuomintang. Founded by a break-off group from the KMT and changed names several times |

|

China Zhi Gong Party |

1925 |

Currently comprises overseas Chinese communities as well as Chinese who have returned from overseas |

Founded in San Francisco by overseas Chinese communities |

|

Jiusan Society |

1946 |

Comprises members largely from top universities across China |

Founded to counter the second Sino-Japanese war aggressions. Aspired to take forward the May 4th anti-imperialist movement |

|

Taiwan Democratic Self-Government League |

1947 |

Comprises people of Taiwanese descent who have settled on the mainland |

Smallest and most recent minor non-communist party in China. It was formed in the wake of Taiwanese Secessionist uprisings. Actively opposes Taiwanese secessionism |

Source: Party Information; Member Demographics

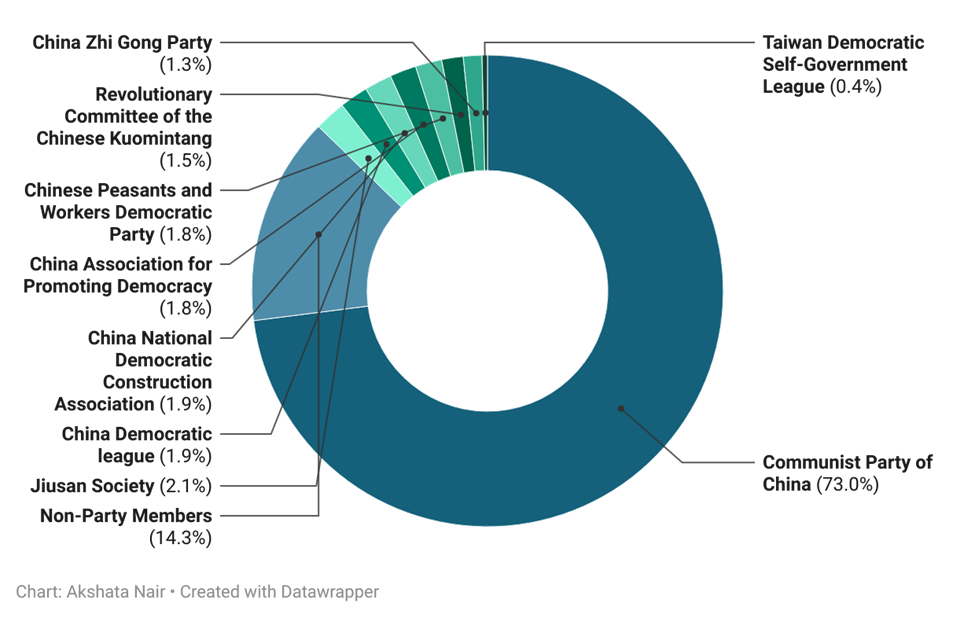

The law-making body, the National People’s Congress (NPC), and its advisory organ, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), largely act as rubber stamp bodies and legitimise the decisions of the CPC. Each non-CPC party has less than 2 percent representation in the NPC. The following graph illustrates the composition of the 13th NPC where the clear majority is held by the CPC, leaving the other parties with no substantial oppositional power. In CPPCC, it is a legal mandate to fill 60 percent seats with non-CPC members.

In the most recent CPPCC, a total of 2172 members were selected. Out of these members, a greater percentage of party members from non-CPC parties. The non-CPC parties combined have nearly 368 members, while the CPC has only 99 members.

Distribution of Seats in the 13th National People's Congress

Source: https://npcobserver.com/2018/03/demographics-of-the-13th-npc/#1998c62ffc29

Membership Criteria for Non-CPC Parties

Membership in the non-CPC parties depend on criteria that vary across parties. Most non-CPC parties ensure a strict eligibility criterion. For instance, the CAPD comprises intellectuals in the fields of education and culture, which becomes an important eligibility criterion for membership. Similarly, the Jiusan society, applicants have to be at least mid-level intellectuals in their field or entrepreneurs to be eligible for membership. In addition to this, a thorough background check by the CPC is mandatory for any applicant to any party. Candidates can contest local elections only after approval from the CPC. On higher levels of administration where direct elections do not take place, the members are appointed by the CPC.

There are two broad aspects of gaining membership in these parties. It is important for members to be at least mid-level intellectuals in their fields and a reference from a senior member of the party is required. The membership of the non-CPC is quite popular because:

- Gaining membership of the CPC is difficult.

- Gaining non-CPC party membership is certainly easier than contesting local elections as an independent candidate, which requires several nominations and approvals from the CPC.

- Citizens have a platform to actively participate in and contribute to governance and policy making.

How do non-CPC parties participate politically?

All the political parties operate under the supremacy of the CPC. This provision is rooted in the Chinese constitution; Article 1 of the Chinese constitution states, “The socialist system is the fundamental system of the People’s Republic of China. Leadership of the CPC is the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Furthermore, the CPC also ensures control over these minor parties through the United Front Work Department (UFWD). The UFWD is responsible for the appointment of the leaders of these minor parties. Through the UFWD, the CPC ensures that no activists, lawyers or other individual with potential to express dissent occupy important positions in these parties.

This inevitably means that no other political party, irrespective of their political ideologies, can gain executive power in China. This leadership of the CPC is constitutionally accepted by the non-CPC parties. This also means that the final say always lies with the CPC. The primary means through which the non-CPC parties engage in multiparty cooperation is through the submission of proposals to the CPPCC. These proposals may be reviewed, accepted, or rejected. The members can file proposals either jointly or individually. Non-CPC Parties actively make use of this method to put forth issues revolving around governance and grievances of the Chinese people. During the 2018-2023 tenure of the 13th CPPCC, over 29,000 proposals were reported to be filed. In the second session of the incumbent 14th NPC, many parties have declared the number and nature of the proposals they intend to submit. The Jiusan Society, for instance, announced a submission of 63 proposals, while the China Democratic League submitted a total of 46 proposals. The CPPPC, therefore, becomes an important avenue to enable the cooperation of the CPC with the non-CPC parties in the governance of China.

This forms the fundamental backbone of the “consultative” and “multiparty cooperation” aspect of China’s socialist democracy. Multiparty cooperation is an important aspect of China’s governance and a distinguishing feature. This multiparty cooperation system serves as a way of legitimising the CPC’s rule. In Chinese white papers on its political system, there is an emphasis on the idea that the multiparty cooperation system enables the Chinese people to collaborate on issues of governance rather than engage in divisive politics that is driven by power dynamics. Therefore, the non-CPC parties’ function to play a consultative role rather than an oppositional one becomes a facet of Chinese society that legitimises the rule of the CPC under the guise of multiparty cooperation, and leaves it unchallenged.

Participation in Policy Formulations

For ordinary members of the non-CPC parties, there exist two broad, institutionalised methods of participating in governance. One method is through a policy survey, which includes a detailed research and action plan for addressing a problem. If approved, the member receives funding to continue the research extensively, and its results are reviewed in the NPC session to find practical solutions. Another way, which is considered prompt, is to provide policy suggestions through a report submitted to the local Department of Political Participation. If the report has merit, it is referred to higher authorities who may consider implementing the suggestions. Participation and suggestions are encouraged by the Department of Political Participation. Members who are higher up in the hierarchy of these parties have opportunity to directly submit their proposals to the local and national people’s congresses.

It is important to note, however, that these parties do not have significant influence over or opportunity for introducing bills related to critical matters such as defence or foreign policy. Each party usually focuses on specific sectors of society. For example, in the 2024 sessions, the TDSL bills focused on economic development and cross-strait relations involving Taiwan. The CZGP bills took up issues like law regarding overseas Chinese citizens, developing and promoting traditional Chinese medicine and the Yellow River Basin. The Jiusan society’s bills targeted the development of scientific research facilities, the development of artificial intelligence as well as construction related concerns on the Yellow River.

To encourage innovative policy initiatives from non-CPC parties, the CPPCC’s Committee of Proposals announces winners of proposals every year for bills that were presented and were of high quality. In 2022, non-CPC parties submitted a large number of bills, out of which some won “Proposal of the Year”. For example, the RCCK submitted a proposal on lowering carbon emissions and increasing reform and innovation in the construction industry. The same year, the CAPD won for a proposal on integrated development of the Yangtze river’s delta.

The approval of these bills depends on the CPC and its decisions are occasionally met with dissent by members of non-CPC parties. An avenue of disagreement, for instance has been with education-related policies. In interviews, members have confirmed that disagreements, when the NPC is in session, are common. Nevertheless, the CPC has the final say in the approval of bills in the legislature. Open opposition of the CPC’s decisions is not something the non-CPC parties engage in.

A point of critique for the non-CPC parties’ political participation has been that they remain largely invisible in Chinese politics. Members from these parties have complained that despite their significant contribution to policy making and problem solving through the available avenues of participation, it is difficult for Chinese citizens to be aware of the tasks they accomplish. Non-CPC parties also have an insignificant social media presence which makes them less accessible to the general public. The most accessible source of tracking their activities is press releases made through state-controlled media. The minor parties’ low profile and inability to gain acclaim is part of the United Front’s strategy to legitimise the rule of the CPC.

Participation at the Local Level

The lower levels of governance in the Chinese system have some provisions for direct election of candidates. Article 97 of the Chinese constitution states that some of the lowest tiers of administrative divisions like counties, cities, municipal districts, townships, ethnic townships and towns shall directly elect their representatives to the local people’s congress. This means that non-CPC party candidates can, with approval of the CPC, contest local elections and be elected deputies up to and below the county level of administration. Article 99 of the Chinese constitution further enables these elected deputies to implement social and economic development plans within the region.

For instance, as of June 2021, over 380 non-CPC officials (which includes the non-CPC party members) held leadership positions on the prefectural and municipal levels of administration. 345 top officials held judicial positions in the prefectural courts. 29 non-CPC officials held the post of vice governors across 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. A few exceptions also exist as some members gain positions in administrative divisions above the provincial level. For instance, the minister of Ecology and Environment, as of June 2021, was Huang Runqiu who is the vice-chairman of the Central Committee of the Jiusan Society. Similarly, Tao Kaiyuan, vice-chairperson of the CAPD, serves as the vice-president of the Supreme People’s Court. The non-CPC parties, therefore, have some opportunity to gain administrative power at different levels of governance.

Conclusion

The multiparty cooperation system under the supremacy of one party is a characteristic unique to China. The political parties can contribute to policy and governance through membership of the NPC and CPPCC while becoming a useful avenue for direct participation of Chinese citizens in government. By functioning within the framework designed by the CPC, the parties legitimise its authority. Overall, the traditional role of an opposition in a conventional liberal democracy is not played by the non-CPC parties in China. It merely serves as organs of governance that allows the CPC to call the Chinese state democratic. For people who are unable to gain membership of the CPC, these parties prove as an opportunity to contribute to policy formulation.